Ngo Dinh Diem Agains Tsouth Vietnma

Southward Vietnam was an independent nation-state, formed in the wake of the Geneva Accords of 1954. S Vietnam became a client state of the United states, supported by American military machine and financial aid. Though nominally democratic, South Vietnamese leaders often subverted democracy and the rule of constabulary in order to maintain and expand their own power, causing problems for their US benefactors.

Germination

Under the terms of the Geneva Accords, North and South Vietnam were to exist for two years as temporary transitional states – at least in theory. In reality, both had already begun to develop into split up national entities.

As this procedure unfolded, the divisions between North and Due south Vietnam widened. This reduced the likelihood of peaceful reunification or free elections to determine future reunification.

The new rulers of South Vietnam were backed by the United states and their Western allies. These men, epitomised past the Christian prime minister Ngo Dinh Diem, presented themselves every bit aspiring democrats and capitalists. Later fighting to remove the shackles of French colonialism, they claimed to desire a free and independent South Vietnam based on Western political and economic values. What unfolded nether their leadership, all the same, was neither democratic or benign to most Due south Vietnamese people.

Ngo Dinh Diem

Ngo Dinh Diem became the prime number minister of S Vietnam in 1954. He was a Catholic and a political outsider who was appointed as leader chiefly due to American manipulation.

From the offset, Diem faced considerable challenges from criminals and political opponents, particularly communist subversives yet active in the southern provinces. Thousands of Viet Minh agents and guerrilla soldiers, near interim on orders from Hanoi, ignored the migration amnesty of 1954-55 and remained underground in South Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh, who doubted the 1956 elections would have place, described these agents as his "insurance".

Opposition to Ngo Dinh Diem could also be found in the military. In November 1954, a clique of officers, trained by and loyal to the French, attempted to remove Diem and install a Francophile military junta. Their insurrection was thwarted past Diem, with the help of the United states of america Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The continuation of the opium trade, some other legacy of French colonialism, also encouraged warlords, organised crime and gangsterism.

Diem assumes power

The newly appointed Diem was determined to bargain with all of these problems, despite his lack of political experience. When Diem assumed power, all the same, South Vietnam was broke and without the organs of government.

During their withdrawal from Indochina, the French had dismantled the apparatus of colonial government. In some cases, entire buildings and departments had been cleared, their contents packed and shipped dorsum to France, all in the space of a few months. The French also stripped South Vietnam of important resources, from military equipment down to telephones and typewriters.

By late 1955, S Vietnam had almost no army, no police forcefulness and very fiddling functioning bureaucracy. Not only did Diem have to persuade the South Vietnamese people that he was in charge but he also had to construct a working system of government.

Diem's nepotism

Without an established bureaucracy or political network, Diem relied on American advisors – and on his own family. His about prominent relatives were his four brothers – Ngo Dinh Nhu, Ngo Dinh Thuc, Ngo Dinh Can and Ngo Dinh Luyen – and ane of his sisters-in-constabulary, Tran Le Xuan (later known in the Due west as Madame Nhu).

Diem gave these family members, friends and political allies important leadership positions in the authorities, military, business and Vietnam'south Catholic church. His closest confidante was his brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, an opium-addicted neo-Nazi who lived alongside Diem in the presidential mansion. Nhu oversaw the creation and organisation of the Regular army of the Commonwealth of Vietnam (ARVN, formed in October 1955) while besides running his own private armies and anti-communist 'death squads'.

In late 1954, Nhu attempted to provide political legitimacy for his brother's regime by forming the Tin Lao, a South Vietnamese party that Nhu hoped would grow to rival Ho Chi Minh's Lao Dong. Tin can Lao never inspired the people or became a popular motion, all the same, and remained relatively small. Membership was merely open to pro-Diem Catholics from the middle and upper classes. In reality, Tin Lao was just a political device to justify Diem's rule.

Corruption and rigged elections

By 1956 Diem'due south authorities had taken clearer grade. Though the Due south Vietnamese government presented itself to the world equally a developing democracy, it was anti-democratic, autocratic, decadent and nepotistic.

There was a National Assembly that claimed to be representative, though rigged elections meant it was nix of the kind. The Assembly was filled with Diem's acolytes and did little more than rubber-postage stamp Diem's own policies. Liberty of the press was curtailed; writing or protesting confronting the government could end in a prison sentence, or worse.

The regime as well eradicated Diem's opponents, under the guise of anti-communist action. Under Nhu's supervision, private armies launched campaigns to locate, arrest and dispose of suspected communists and sympathisers in South Vietnam. Thousands were rounded up, deported, tortured, thrown in prison or executed. According to some sources, more South Vietnamese were killed during Diem'due south four-yr anti-communist purge than during the Showtime Indochina War of 1946-54.

In May 1959, Diem issued the notorious Law 10/59. This prescript empowered armed services tribunals to impose a capital punishment on anyone belonging to the Viet Minh, Lao Dong or any other communist organisation:

"Commodity i

The sentence of death and confiscation of the whole or part of his holding will be imposed on whoever commits or attempts to commit one of the following crimes with the aim of sabotage, or upon infringing upon the security of the Land, or injuring the lives or property of the people:

i. Deliberate murder, food poisoning, or kidnapping.

2. Destruction, or total or fractional damaging, of … objects past means of explosives, burn down, or other ways

Article 3

Whoever belongs to an system designed to help to prepare or to perpetuate crimes enumerated in Article 1, or takes pledges to do so, will be discipline to the same sentences."

Rural reforms

The Diem regime also embarked on social reorganisation it hoped would disrupt communist influence. In 1959, the Saigon authorities introduced the Rural Community Development Program, or 'Agrovilles' (khu tru mat). This was effectively a plan of mass resettlement: peasants in small villages or isolated areas were forced to relocate to populated areas under government control. Information technology had some similarities to Soviet farm collectivisation, though its objectives were more political than economical.

Past the early 1960s, there were more than two dozen Agrovilles in S Vietnam. Each independent several thousand peasants, nigh driven there at the bespeak of a gun, from villages which had previously contained but a few families.

The Agroville resettlements caused enormous social and economical disruption. Families were separated, shifted from familiar territory and forced to abandon important spiritual sites, such every bit temples and ancestral graves. Most of these Agrovilles were besides small for everyone to be given plots of land or employed as farmers, meaning there was little or no work.

'Strategic hamlets'

In 1961, the 'Agroville' scheme was transformed into 'strategic hamlets' (ap chien luoc). This was suggested to Diem past American advisors and developed largely by the CIA.

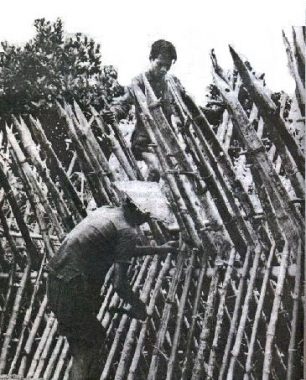

The strategic hamlets were intended to exist a network of self-sustaining communities, potent enough to withstand communist infiltration and attack. Peasants would be moved into these large rural settlements; they would be compensated for this relocation and allocated plots of land. Each strategic hamlet would be provided with a defendable perimeter, pocket-sized arms and militia training; it would be outfitted with a radio or telephone connection to make contact with the regime, ARVN and nearby hamlets.

Like the Agrovilles, the strategic hamlets programme failed, chiefly considering it was poorly implemented. Despite a barrage of CIA-produced propaganda, about peasants did non wish to relocate. Much of the money prepare aside for compensation ended upward in the pockets of decadent government officials – including Diem's own family – instead of beingness distributed to the peasants.

By late 1963, the South Vietnamese regime claimed to have completed viii,600 strategic hamlets, nevertheless, a subsequent American investigation constitute four-fifths of these were incomplete. American funding dried up and the program soon faded abroad. Many strategic hamlets were abandoned, stripped of whatever was useful and left to rot.

Other economic reforms

Despite its failures and rampant abuse, the Diem government did brand some progress in industrialising the economy. Due south Vietnam'south status as a developing nation recovering from war and colonialism received all-encompassing media coverage in the Westward. This prompted many Western companies to aid Saigon with trade and investment.

In 1957, Diem announced a 5-twelvemonth economic plan and called for foreign loans and domestic investment. Those who invested in the South Vietnamese economic system, particularly its export industries, were promised government guarantees and concessions, such every bit lower taxation rates and land rents. Local companies were subsidised and locally produced goods were protected with tariffs. Meanwhile, the government and its agencies imported much-needed equipment: factory and agricultural machinery, motor vehicles and raw materials such as steel and ore.

South Vietnam's agricultural sector also recovered. Rice production boomed, growing from 70,000 tons per annum (1955) to 340,000 tons (1960). Predictably, Diem's master trading partner during this catamenia was the United states of america. Between 1954 and 1960, the US government pumped around $US1.2 billion into Southward Vietnam, about 3-quarters of which was used to expand and bolster the military. Washington also offered incentives to American companies willing to trade with South Vietnam.

Diem's persecution of Buddhists

The relative success of Diem's economic programme enabled many to overlook the brutality and excesses of his government. Information technology was Diem's persecution of another group – Southward Vietnam'due south Buddhists – which made headlines around the globe and spelt the first of the end for his regime.

More than three-quarters of the South Vietnamese population was Buddhist. Despite this, it was minority Catholics who benefited almost nether Diem's government. Government officials, loftier ranking military officers, business concern owners and landlords in receipt of government assistance were overwhelmingly Catholic. Many fifty-fifty converted to Catholicism just to win favour with the regime.

In May 1963, on the eve of Vesak (a celebration of Buddha'southward birthday), Diem issued a decree banning the brandish of religious flags in public. Thousands of Buddhists in Hue rioted in response. The demonstration was brutally dispersed by government forces and viii people were killed.

Vietnamese Buddhists protested their treatment with a series of rallies, sit-ins and hunger strikes. In June, Diem'due south forces dealt with i protestation by using tear gas and pouring battery acrid on the heads of seated Buddhists. In July, a grouping of American journalists roofing Buddhist protests were involved in a fistfight with a grouping of Diem's secret police. These incidents started to betrayal tensions between Washington and Saigon.

Thich Quang Duc

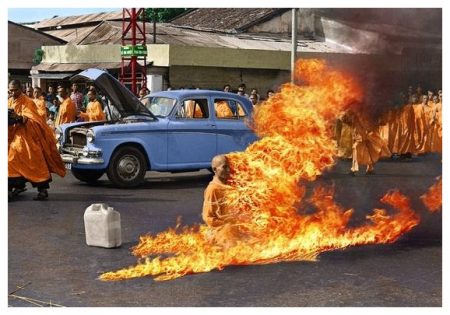

The most striking Buddhist protestation occurred on June 11th 1963. In the center of a busy Saigon street, a Buddhist monk named Thich Quang Duc calmly sabbatum downward and delivered a short spoken communication, after which a colleague doused him in gasoline. Duc then set himself alight and sat motionless every bit the flames engulfed his body.

Images and footage of Duc's suicide were circulated worldwide. His cocky-immolation drew attention to the Buddhist plight in South Vietnam and the corruption and inherent brutality of Diem's government. Fifty-fifty this did non halt Diem's anti-Buddhist programme.

In August, shortly earlier a major Buddhist protest rally in Saigon, Diem declared martial law in the city. He authorised ARVN forces to raid Saigon'southward Buddhist pagodas and abort suspected "communist sympathisers". Hundreds of Buddhists were arrested and many vanished, probably murdered. Thousands more fled and their pagodas were desecrated by Diem's troops.

In Washington, the situation in South Vietnam was at present considered untenable. Diem seemed almost uncontrollable and his regime was a constant source of bad news and negative publicity. In late August, but days after the anti-Buddhist raids, president John F. Kennedy asked the State Section to investigate the options for 'authorities alter' in South Vietnam.

A historian'southward view:

"[Usa ambassador to Due south Vietnam] Henry Cabot Lodge arrived in Saigon on August 22nd 1963 [and] delivered his ain speech [to Diem]. "I want y'all to be successful. I want to be useful to you. I don't expect you lot to be a 'yes human being'. I realise that you must never appear a boob of the United States." Notwithstanding, he insisted that Diem had to confront the fact American public stance had turned against him. The U.s.a., Lodge asserted, 'favours religious toleration', and Diem's policies were 'threatening American back up of Vietnam'. Diem had to set his house in order, and that meant removing his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu, silencing Madame Nhu, punishing those responsible for the May massacre in Hue, and conciliating the Buddhists. Washington was no longer prepared to support the Diem regime unconditionally."

Seth Jacobs

1. Betwixt 1954 and 1963 South Vietnam was a nominally autonomous republic, propped up by American political and fiscal support. In reality, there was petty democratic about its government.

2. Due south Vietnam's leader, Ngo Dinh Diem, claimed to caput a democratic government. In reality, Diem was a petty dictator, assisted by family members, Catholic acolytes and US advisors.

3. During his dominion, Ngo Dinh Diem authorised savage campaigns confronting his political enemies, peculiarly suspected communists (1955-59) and Vietnam's Buddhist monks (1963).

4. Diem's social programme included the failed 'Agroville' and 'strategic hamlet' resettlement programs. His economical reforms, helped by foreign trade, were more successful.

5. The United States supported Diem and his regime with advisors and money, however by Baronial 1963 Diem was a liability and Washington began investigating ways to remove him.

Citation information

Title: "South Vietnam"

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/vietnamwar/southward-vietnam/

Engagement published: June 23, 2019

Date accessed: April 17, 2022

Copyright: The content on this folio may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.

Source: https://alphahistory.com/vietnamwar/south-vietnam/

0 Response to "Ngo Dinh Diem Agains Tsouth Vietnma"

Post a Comment